JD.com Falls Back on Logistics in Southeast Asia After E-commerce Defeat

The Chinese e-commerce giant entered Southeast Asia in 2015 through a joint venture with an Indonesian investment firm, but the local competition proved too tough

Key Takeaways:

- JD will cease operations in Thailand on March 3 and in Indonesia on March 31, but will stay active in the region as a logistics services company

- After eight years in the region, the e-commerce platform has far fewer users in those markets than Alibaba-owned Lazada and Tencent-backed Shopee

By Fai Pui

In January 2020, Richard Liu, founder of No. 2 Chinese e-commerce platform JD.com Inc. (JD.US; 9618.HK), said in an internal letter that international expansion, doing business in rural areas, technology and services were “must-win battles”. Now, he might need to rethink that, following a major retreat from one of his first major overseas forays.

Rumors began swirling as early as November that JD.com’s international unit would close its e-commerce businesses in Indonesia and Thailand in the first quarter of this year and had started laying off employees. On Jan. 30, the company’s Indonesia and Thai units separately announced on their websites that the former would stop taking orders from Feb.15 and cease operations on Mar. 31, while the latter would end operations as early as March 3.

JD said that despite the e-commerce retreat from Southeast Asia, it would continue to ramp up investment in warehousing and logistics in region, as well as in Europe and North America. It added it would continue to provide services to global markets, including Southeast Asia, through its supply chain infrastructure.

The moral to this e-commerce story might be that JD.com was “out-localized” in the region by rivals Alibaba (BABA.US; 9988.HK) and Tencent (0700.HK), which are both doing far better through their ownership and investment in two of the largest local players, Lazada and Shopee.

Liu started his global foray as early as 2015 in Southeast Asia, a market with close to one-tenth of the world’s population. He chose Indonesia as his first stop, attracted by the nation’s rapid economic development. Things went swimmingly at first, as the products on JD.ID, its joint venture with Indonesian investment firm Provident Capital, grew tenfold in just over a year.

JD adopted a model relying on self-operated logistics and third-party merchants to quickly boost its presence. That required far more effort than Alibabaput in for its acquisition of Lazada and Tencent’spurchase of astake Shopee, now two of the region’s leading players. Liu once said it would only take five to 10 years for JD.ID to replicate the success of JD.com in China.

Two years after entering Indonesia, JD launched its e-commerce business in Thailand through two joint ventures with major local retailer Central Group, which held 50% stakes. The remaining share was split between JD’s financial arm and Provident Capital.

Insurmountable Big Three

But instead of becoming another regional e-commerce giant, JD.com’s two Southeast Asian forays have spent much of the past eight years living in the shadows of the current “big three” of Lazada, Shopee and Tokopedia. More recently the site blibli has also been an up-and-comer in the region.

Among the big three, Shopee had 544 million visits last October through December, Tokopedia had 405 million, and Lazada had 224 million, according to internet data tracker SimilarWeb. Even blibli had 101 million visits. But JD.ID had only 5.8 million. In terms of time spent shopping, Lazada, Shopee and Tokopedia boasted average times of 4 minutes to 6 minutes, while JD.ID’s average was only 2 minutes and 28 seconds.

Chinese tech companies will need to adjust their strategies to better suit local cultures in order to succeed globally, especially in the Southeast Asian market that shares cultural similarities with China but is also fiercely competitive, said Kenny Wen, KGI Asia’s head of investment strategy.

“It is not easy to challenge the leading local companies, as many countries have business restrictions that sometimes favor local companies, or set high policy barriers for foreign rivals to enter the local market,” Wen said.

Despite its large size, many Southeast Asian countries are indeed biased towards local companies – a practice often seen in both developed and especially developing countries. Foreign companies like JD that want to enter those markets may have difficulty getting necessary business licenses, leading many to seek local joint venture partners to gain the government’s trust.

But such joint ventures are often prone to disagreements between shareholders on how to operate the business, especially in areas like local hiring and day-to-day management. Meanwhile, foreign partners like JD must also deal with different local customs such as different attitudes toward working overtime, and preference for a slower pace of life. JD was even forced to change its puppy dog logo to a pony due to the negative image of dogs in Indonesia.

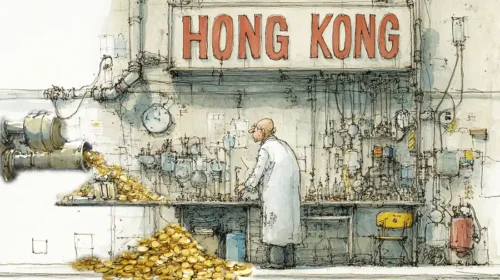

Focus on warehousing and logistics

Before its decision to withdraw, JD was investing heavily in logistics infrastructure in booth Indonesia and Thailand. But with the company making little headway in e-commerce, it is pivoting to focus those resources on the local warehousing and logistics business. The company’s separately listed JD Logistics (2618.HK) already has such a focus in its home market.

According to media reports, the company’s JD Property subsidiary has invested in and manages 20 logistics parks in Indonesia, with overall area of over 400,000 square meters. Last year, JD Logistics even deployed a new self-operated warehouse in Malaysia, focusing on providing services to merchants.

After more than a decade of rapid growth, China’s homegrown internet companies are trapped in a saturated market and subject to occasional government crackdowns. They’ve tried looking for growth in the global market, though without much success due not only to local competition and bias, but also other political factors such as China’s recent tensions with the west.

The political element isn’t limited to the west, either, as illustrated by a recent case involving smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp (1810.HK) in India. Xiaomi was one of the first Chinese smartphone makers to enter India and quickly became the market’s biggest brand. But the government accused it last year of tax evasion, and eventually froze $676 million of Xiaomi’s assets pending resolution of the dispute. That forced Xiaomi to close one of its Indian production lines due to lack of cash.

Despite its Southeast Asian setback, JD’s broader outlook is still quite promising. The company delivered good results in last year’s third quarter despite numerous Covid-control disruptions in China, with revenue up 11% year-over-year to 243.5 billion yuan ($35.9 billion) and a net profit of 6 billion yuan. While it’s giving up on Southeast Asian e-commerce, at least for now, many will be watching closely to see if JD can have better luck in the region in the warehousing and logistics business in the post-Covid era.

To subscribe to Bamboo Works weekly free newsletter, click here