China Renaissance Chairman’s Vanishing Act: A Warning for Private Financiers?

The venture capital firm’s shares lost half their value after its chairman and rainmaker Bao Fan went missing

Key Takeaways:

- The disappearance of China Renaissance founder and Chairman Bao Fan is drawing attention to risks associated with investing in private Chinese financial companies

- Some reports said his disappearance was linked to investigations of others for corruption, and wasn’t the result of allegations against him

By Lau Ming

China constantly says it’s committed to supporting its private sector. But every now and then something happens that reminds investors that such commitment comes with many caveats.

That was certainly the case when legendary investor Bao Fan, founder of venture capital firm China Renaissance Holdings Ltd. (1911.HK), was reported missing in action last week. Such disappearances almost always mean the “disappearee” is suspected of a crime, or may be assisting in an investigation of someone else, and it remains unclear which of those may be the case for Bao.

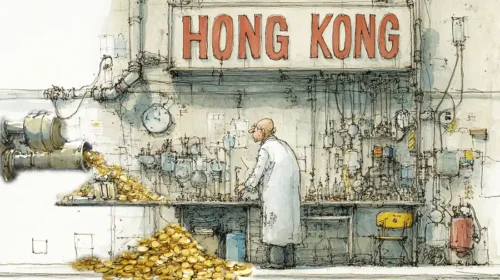

Either way, the incident shows how business leaders in the Wild West also known as China’s financial industry can vanish at any time in China’s current climate of zero tolerance for corruption. When such disappearances happen, the news can cause stocks to plummet, presenting a unique risk associated with China’s publicly listed private financial companies.

China Renaissance confirmed late Feb. 16 that Bao, its chairman and controlling shareholder, could not be reached. It emphasized the company was maintaining normal business operations, but that didn’t really do much to calm investor nerves. After the news broke, its shares nosedived as much as 50% the next day before rebounding a bit to close down 26%.

Bao is Renaissance Capital’s controlling shareholder, holding 48.76% of its shares directly or through entities he controls. He is known for his accomplishments in China’s venture capital community, and is sometimes called the country’s “king of M&A”. He cut his teeth on Wall Street at major banks like JPMorgan and Credit Suisse, before setting up his own shop with China Renaissance in 2005.

The company quickly established itself as a major player after helping to broker multiple major M&A deals in China’s internet sector, including combinations that led to the formation of the current Uber-like Didi Global (DIDIY.US), takeout dining giant Meituan (3690.HK) and 58.com, a company often called the “Craig’s List of China.”

Not guilty?

After Bao went missing, some reports, citing information provided by inside sources, said his disappearance was related to misconduct involving former Renaissance Capital Chairman Cong Lin, suggesting he was not personally suspected of any crimes but instead was assisting in the investigation of Cong.

Meanwhile, the company’s creditor banks, including SPD Bank, Bank of Communications, CITIC Bank and China Merchants Bank, reportedly asked the company to provide more information about Bao’s current whereabouts, and even tried to obtain more information through legal channels to better assess their exposure to the company via their loans and other business dealings.

CITIC Bank, China Merchants Bank, Bank of China and Nanyang Commercial Bank made a $300 million syndicated loan to Renaissance Capital in May 2021, and can ask the company to repay any outstanding funds unconditionally if Bao is no longer chairman or the company’s biggest shareholder. Thus, Bao’s whereabouts could have a direct impact on the company’s finances if he has to relinquish his chairman’s role.

“Such risks are hard to avoid when you invest in Chinese private companies,” said a veteran investor familiar with the Hong Kong stock market, speaking on condition of anonymity. He added it’s common in China for companies to engage in “dubious activities” to secure business or development opportunities, and many people in finance have been forced to passively become involved in such activities.

Another financial sector source said successful M&A deals in China often require management of the acquiring company to have the right connections, which are often more important than having the necessary financial resources. Companies with the right political and business connections tend to find the best projects, and have an easier time getting them approved by regulators.

Similar case

Bao’s case isn’t the first time a famous Chinese financier has gone missing. On Dec. 10, 2015, Guo Guangchang, chairman of Shanghai-based Fosun Group and a man sometimes called the “Warren Buffett of China,” also vanished, and was rumored to be assisting in the corruption case against former Shanghai deputy mayor Ai Baojun. The incident rocked Fosun, leading to the trading suspension of its flagship Hong Kong-listed investment vehicle, Fosun International (0656.HK), on Dec. 11. The company held an emergency conference call two days later.

Guo re-emerged on Dec. 14 to give a speech at Fosun’s 2016 annual meeting, but made no mention of his disappearance. Fosun International’s stock resumed trading that day but still lost 9.5%, suggesting the market wasn’t completely reassured by his reappearance.

A more severe incident occurred in 2018 when Wang Jian, chairman of the former highflying HNA Group, which was crashing under a mountain of debt at the time, fell to his death at a tourist site in France. His death came to be known as HNA’s “first drop of blood” in Chinese executive circles, and the company later ended up selling off many of its domestic and Hong Kong assets to reduce its debt.

The website of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist Party of China, the country’s anti-corruption watchdog, shows nearly 70 individuals from the financial sector were stripped off their party status and positions for wrongdoing in 2021. The body ratcheted up its war against corruption even more with the behind-the-scenes detention in Hong Kong of Xiao Jianhua, controller of the troubled Tomorrow Group. That anti-corruption campaign focused on the financial sector has led to more senior executives of mainland and Hong Kong-listed companies being asked to assist in investigations, with Bao as the possible latest case.

Bloomberg recently reported the chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) Yi Huiman might become the next chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), with Shanghai deputy mayor Wu Qing taking over his position at the CSRC. Wu played a key role in an earlier crackdown on the financial sector, overseeing the shuttering of 31 brokerages over regulation breaches in his previous function as head of the CSRC’s risk disposal office, a title he took in 2005.

After becoming chief of the CSRC’s department of fund supervision in 2009, he led another clean-up effort by investigating suspicious trades by mutual funds, leading to the exposing and punishment of a number of fund company officials. His tough tactics earned Wu the moniker of “broker butcher.” Now, his potential new position as head of the CSRC might pave the way for more stringent regulatory policies on brokerages and other financial firms, which could undermine China Renaissance further still.

To subscribe to Bamboo Works weekly free newsletter, click here