Alibaba’s international business set for growing pains with spinoff, separate listing

The e-commerce giant is reportedly talking with banks about a separate U.S. listing for its money-losing global e-commerce unit next year

Key Takeaways:

- Alibaba is reportedly weighing a spinoff and separate listing for its offshore e-commerce operations as part of a massive corporate restructuring plan announced in March

- Such a move would let the loss-making international unit set its own strategy, addressing the localization challenge, but would also force it to stand on its own financially

By Trevor Mo

Alibaba’s (BABA.US; 9988.HK) money-losing international e-commerce unit is getting a quick lesson in growing up.

Just weeks after the internet giant announced its biggest corporate restructuring since its founding, the company has reportedly initiated a process to spin off and separately list its offshore operations. Such a move, first reported by Bloomberg last week, would bring both advantages and challenges for a brave new company whose main assets would include Alibaba’s Southeast Asian Lazada service, as well as its AliExpress that connects global buyers with Chinese e-commerce merchants.

Chief among the advantages would be greater flexibility in running businesses covering a range of diverse markets from Southeast Asia to Pakistan and Russia. Such flexibility is sorely needed right now, as growth at those businesses slows sharply for reasons we’ll discuss shortly.

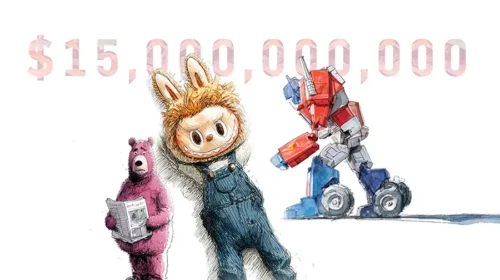

Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. first disclosed its bigger breakup plan in late March, saying it would transform into a holding company with six separate operating units, one of which was its international e-commerce business. The other five were: digital media and entertainment; local consumer services; logistics services; cloud computing; and China commerce. It said the move would make its operations “lighter and thinner.”

The Bloomberg report looks like an extension of the original announcement, saying Alibaba is in talks with banks to potentially prepare the international unit for a U.S. IPO next year.

While the new holding company would probably still hold controlling stakes in the international business, as well as the other five units, the breakup is still significant for its implications for the future evolution of all six businesses. The company previously said each of the six will have its own management team and autonomy to set business strategy.

For the international team, a separation from its dominant – and highly profitable parent – means it will have more flexibility to set its own agenda. A potential IPO would also allow it to tap public markets to raise some much-needed cash to fund its future development, including potential expansion into other markets and services.

Such spinoff would also force the unit to stand on its own, reflecting an effort to breathe new vitality into a business that has achieved mixed results despite Alibaba’s years of effort and devotion of major resources to expanding beyond its domestic market. A spinoff and separate listing could also help to ease some foreign governments’ concerns about data security, since Lazada, AliExpress and the other international assets possess huge troves of such data in the markets where they’re active.

Global ambitions

Alibaba’s global ambitions have been well known for years, with founder Jack Ma famously proclaiming in 2017 that his company aimed to serve 2 billion global consumers by 2036. But despite dominating its own home market, the company’s years of effort at global expansion have yet to start producing such big numbers. Lazada is a major player in Southeast Asian e-commerce, but has seen its early lead in the region eroded by Sea Ltd.’s (SE.US) Shopee.

Research from iPrice Group shows Shopee overtook Lazada as the region’s most used online shopping app in 2019, and has been downloaded more often in the years since then. Another recent survey by McKinsey also showed Shopee continues to beat Lazada in popularity in Vietnam, with 74% of the respondents saying they frequently shop on the site, versus 48% for Lazada.

Cross-border e-commerce platform AliExpress is also having its own issues lately. Notably, the service has suffered a major setback since early last year in Russia, its largest market, caused by restrictions resulting from western sanctions after the country invaded Ukraine.

On a broader basis, growth momentum for Alibaba’s overseas businesses has slowed over the past two years. In the three months through December, combined orders on Lazada, AliExpress, the Middle East focused Trendyol and South Asia-focused Daraz grew by just 3% year-over-year, the company previously reported. That’s a sharp slowdown from the 34% growth rate for the 12-month period through March 2022, according to the company’s financial reports.

For its fiscal 2022 year, the international unit recorded an EBITDA loss of 9 billion yuan ($1.3 billion). Even if it could raise funds through a future IPO, the international unit would no longer be able to count on Alibaba’s profitable domestic e-commerce business to come to its rescue with financial assistance following a spinoff.

That brings us back to the question what a spinoff for the international business might mean for the next phase of Alibaba’s global expansion. The greater autonomy we’ve previously mentioned would allow Alibaba to continue delegating more power to its local teams to manage their businesses. This could help to improve localization efforts that are often cited as a major reason behind a relative lack of vitality for the overseas operations.

The locational challenge is most prominent at Lazada. After investing $1 billion for 57% of the Southeast Asian platform in 2016, Alibaba continued boosting its investment to bring its stake to the current level of 90%. As its stake increased, Alibaba also began sending more personnel from its mainland China base to Southeast Asian countries, rapidly diluting a previous management team that was mostly locals.

Alibaba may have hoped that introducing mainland managers would help Lazada replicate the parent company’s success in its home China market. But such a strategy hasn’t been quite that smooth, and many Chinese staff were sent back to the mainland after meeting resistance from locals, according to a reportby local media PingWest.

While Alibaba touted its bigger break-up plan as aimed at turning itself to a leaner organization, another subtext was whether such a breakup might appease Chinese regulators that have grown increasingly distrustful of the power wielded by the nation’s big tech companies.

In this case, Alibaba may find that regulators are unconvinced, if its purpose in letting its international unit list and operate separately is to prove it is really “breaking up” by giving the unit more autonomy. That’s because Alibaba will likely retain controlling stakes in all of the businesses being spun off for the foreseeable future, despite CEO Daniel Zhang’s promise to gradually give up control of some of the businesses.

At the end of the day, flexibility to make independent business decisions will help the international unit, but may not be enough to help it to truly take off. More importantly, massive investment may be needed to expand the unit, which remains stuck in the red and unable to generate much cash.

To subscribe to Bamboo Works free weekly newsletter, click here